on middlebrow art

#Scurf226: as a small town someone, this was gateway into the world of literature, poetry, music and cinema and i will never grow out of it

What we loved was not meant to be loved. It was the stuff of secondhand embarrassment, a kind of culture that’s all cringe and cliché. We would watch B grade Hindi films in our parents’ absence, glued to late-night radio listening to all shades of romantic, sleazy Hindi movie songs, devouring books that would never be called literature. Growing up in a small city, there were no grand cultural spaces, no spotlights to be found. In a way I had to make my own culture, to find my own niche, to love the things, I would later realize I was supposed to be ashamed of.

Parents gave no pocket money, hence whenever I found some, or was gifted any, I’d run to the closest cassette store to buy the recent music album or buy the most pink-ishly decorative looking scholastic book from the school fair. It almost always felt that one was outside of culture. Trying to grasp at something in the dark.

When my friends began to see movies together, I was rarely included. I was the one left behind, too dorky to be part of the group, too shy. The movies they watched without me — Rang De Basanti, Jhoom Barabar Jhoom, Cheeni Kum, Jaane Tu Yaa Jaane Na — are more real to me than the ones I did see with them. I’m haunted by the movies I didn’t get to see with them. They are bigger in my culture cache than the ones I did end up watching — Woh Lamhe, Lakshya, Jannat, Gangster.

This essay is a way to put a intellectual framework for the appreciation of the middlebrow. The simultaneous feeling of embarrassment and pleasure that comes from watching these films — a feeling that is both rejection and surrender. As if it is our base nature to squirm and yet to enjoy, to be repelled and drawn in all at once.

I would add here that the access small city kids like me had to culture back in the day was really appalling, abysmal, you get the gist. I remember being so bored, especially on Sundays when both parents were off from work and we had to pretend to have a timetable and to study or to just *behave*. The boredom would sometimes hit me hard immediately after waking up and I’d start by reading every corner of the newspaper. The language in the newspaper — Hindi or English — was what mattered. From the op-ed pages I’d find a quotable quote they’d publish every Sunday and write it down into my notebook. To stroke my bored brain into some form of engagement, I’d read the movie listings and advertisement competitions for expensive ice creams with equal awe. I’d spend hours scouring through these in a way that made would quench my thirst (or was it hunger?), in a way that’d make me feel as though I’d watched those movies and eaten those ice creams. Imagine being bored enough to imagine watching movies and eating ice creams. This is not to wax poetic about that form of generative boredom, but just to give you a sense of the provincial small town’s limitations for kids.

No, we didn’t ever have access to Nat Geo magazines or Readers Digests. So much so that when I first got my hands on a copy of an old worn out nearly discarded copy of Readers Digest I remember feeling the awe at reading a joke there (I remember the joke verbatim till date). We always had those religious journals and pamphlets, which by way of reading to satisfy parents, we’d had licked off all out!

Then, it was these grungy, small, slightly corny movies that came to my rescue. Years ago I wrote about the literary nature of cinema and how it could and should also be considered literature. And this will build on that. In that boredom, I didn’t just watch those movies, I almost read them, sans subtitles, sans any cultural alienation, sans any other form of engagement.

These movies were the only way in which I connected with a world outside of my own. The way people talk fondly about having read this or that book as kids (here’s looking at you readers of Little Women, Middlemarch and all the likes), I fawn over the movies that provided me with that outlet of imagination. I remember my face being slack jawed, eyes glued to the TV that was stealthily turned on in parents’ absence and being physically pulled out of my body and mind into the landscape of that very terrible or barely watchable movie onscreen. I had access just to school library books and it felt like there was an active effort from the school’s side to stifle imagination by making us read Cinderella and Aesop’s fables in standard 3 (age 8-9).

Then there were relatives, our governess and the paraphernalia of out of work cousins who lived in our joint family that made us watch movies with them whenever we were in their care. They thought they were forcing us to watch movies to keep us quiet, they didn’t know they were planting seeds for future discerning cinephilia. Dil Se was a movie I watched with my aunt when parents had to travel out of city for work (or for a wedding, who knows!). There was also the fact that I’d sometimes find ticket stubs of highbrow art films my parents had gone to watch without telling us. Secret movie dates watching movies like Fire, Monsoon Wedding, Water, Earth. Somehow these highbrow art movies have completely vanished from the Indian landscape.

While parents pursued discerned highbrow cinephilia in their spare time, us kids at home pursued the purloined pleasures of lowbudget commercial cinema. Some of it as cheesy, mainstream, noisy, as masala as your chicken tiki taka masala can get. Some of it as smooth, milky yet sophisticated as that rare cup of good chai from a streetside stall. These films I’d later learn were classified as B-grade Hindi movies that were made in lowest of low budgets (mid), featured not so famous actors (mid-er) and mostly new faces as leading ladies that’d almost always charm the socks out of our prepubescent hearts in small cities (rad-est).

The characters would be based in small towns like mine, girls hailing from families of similar or worse background with little or no careerist aspirations but dreams of making it big in the land of heart and love and valor (wherever that was). Storytelling structured around the knick-knacks that made up our everyday in middle class households. The movies were even shot in the reachable and graspable environs of Singapore, Hong Kong and Bangkok. Not the snow clad background of Switzerland and UK. There was little to no glamour in this disparagingly called middle of the road movies, but the story was strong, the pathos relatable and goals always the same.

Gangster, Awarapan, Woh Lamhe, Jannat 1, 2, Life in a Metro, Kalyug, Murder — you name them they got it. As much for their stories, these movies remain ever so special for their songs. The lyrics, compositions, singers — everything. I can clearly recall the day, hour, minute and company where I first heard them. It’s pristine, the stuff of rhapsodic journal entries. Watching a pirated copy of Gangster on our brand new CD player I realised how much I loved not only the sincerity of Emraan Hashmi’s Aakash that stood at odds with the ruggedness of Shiny Ahuja’s Daya. The endlessly sad, perennially drunk and gorgeously dressed Kangana Ranaut’s Simran, sitting by the river front in Bangkok — these movies took me out of the stifling environment of my parents’ house and into the world of murder, crime and romance.

Each one of these movies were made from a place of earnestness that begets immediate recognition. They struck a chord with me in that moment of deep adventure, loneliness and melancholy. Woh Lamhe was a formative movie in my cinephile journey and I still cherish that experience of watching it with a group of some 14 friends none of who actually really or even superficially saw me. In that womblike aloneness of the cinema hall I had felt seen by the quick ascension of Kangana’s character from being a nobody to an overnight star. There was recognition in the fact that anybody could do something. At my lowest, that movie gave me hope.

There’s a common thread running through all these films — Vishesh Films, the studio that showed faith in these stories. Two decades later, I still feel cradled by the songs from these movies.

A dialogue from a recent Hindi movie fits here somewhat:

“The songs that move us have a special moment behind them. They capture what is felt in that special moment. Those lyrics when written down on the proverbial empty page make us travel with them, sometimes taking us as far as back to our childhood, sometimes to our first love, sometimes to the first time we experienced rain. And you know what? All our memories that are borne out of these songs are lodged somewhere in a corner of our heart, in the heart of our hearts. And that song, it brings us out of ourselves and in the midst of these memories to take us back to those times. Because the mind forgets but the hear remembers.”

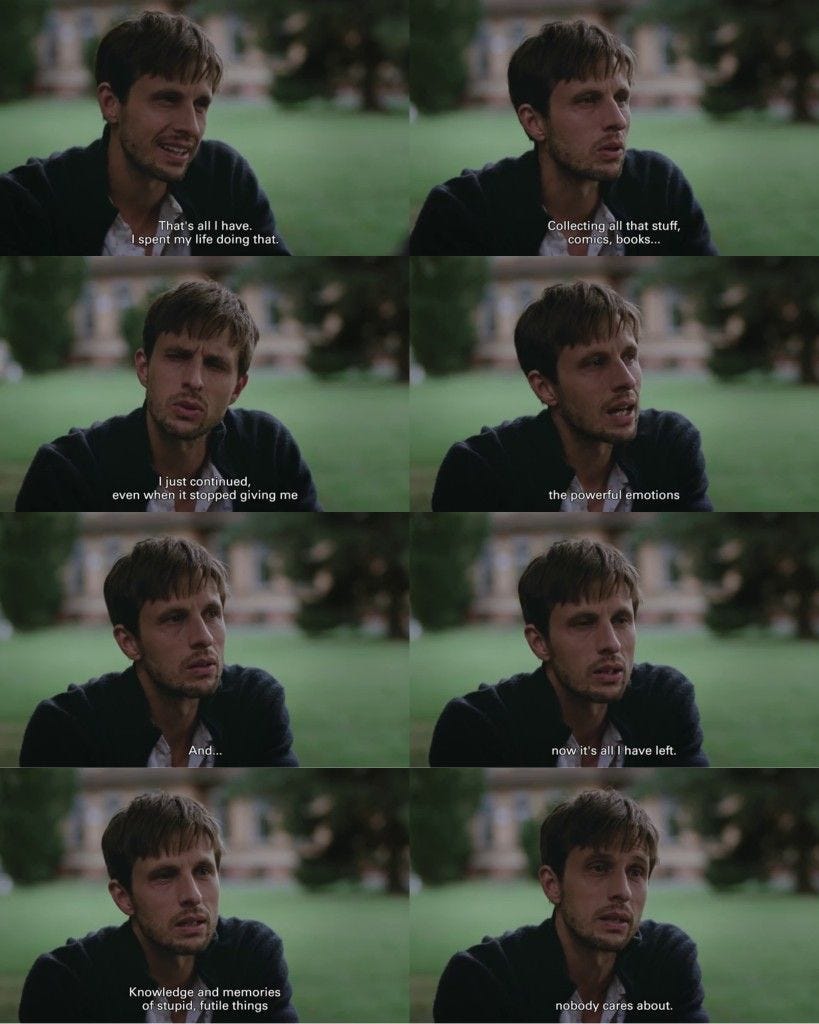

This rings true for movies, books, comics, everything irrespective of what class of art it belongs to. And brings me to a recent exchange at the city library: I have been searching for a physical copy of a book for many months, looking up library catalogues in person and online. Sometime last month, I was finally feeling very exasperated with various other things and wound up actually asking a librarian to help me locate the book. When I told him the title and author’s name, he smiled, saying he knows the novel and has seen the movie made on it. I was beyond myself, having arrived at the book via the movie myself. “Yes, the Louis Malle film!” I chirped. “No, there’s a Norwegian movie too.”

I was beside myself by now because I had foolishly assumed who would’ve bothered watching this tiny obscure Norwegian movie I’ve been obsessed with since I first saw it in 2022. Trying to hide my joy, I went: “Oh yes of course! The Joachim Trier film!” And then we went on for a bit chatting about the movie, forgetting momentarily about the book.

Cut to 2025 when these cherished middle of the road movies have been taken away from us for quite a few years, a new Hindi movie makes the heart feel full. As the weekend leaves, I’m satiated for once. It just arrived on Netflix and I pressed play the moment I saw it on the homepage and it felt like coming home right from the start. The soundtrack equal parts soulful and melodious. It’s innocence and high-voltage drama envelopes me. There’s so much earnestness, power in the story and decibels in the acting, what’s there not to love! No wonder this movie cast that spell on people in India, and has completed a run of showing for over 50 days in theaters. There’s a special place in all of our misanthropic hearts for those cloying, puppy love stories done well. And Saiyaara does just that, with a near perfect soundtrack.

On an unrelated (?) note

I might’ve spent an inordinate amount of time watching Uberlin on repeat this past week. It never gets old, and the lyrics “let’s get on the U-bahn” almost always make me chuckle. How un-ubiquitious culture was at that time, every video in the same album so remarkably different from the one before. The choreography so singular, the light so basic yet alluring, each frame reminiscent of a dream you’ve had or could have at some point in the future. Probably explains why with time eroding itself so rapidly right now, I find myself reaching out to old music — music my father loved (Suraiya, Hemant Kumar, Rafi, Kishore), music my aunts listened to (Abba, Bee Gees, Boney M, Freddie Mercury), music I taught myself (Geeta Dutt, Hemant Kumar, Kishore, Rafi, R.E.M., The Kinks, Laura Marling, early Sonu Nigam, all of AR Rahman’s Tamil & Hindi, Bally Sagoo). Rest is all just a reel. I could go on, but so we wrap!

Moth season came and went, but inside my phone’s gallery and my mind’s corners, its moth season all year round. Hence a short reading list:

Pia Ghosh Roy’s Separated by the Wingspan of a Moth (link is lost forever)

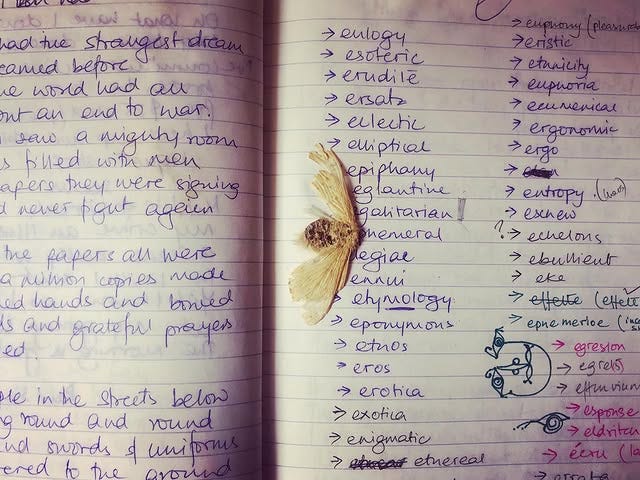

This post is from Koko’s ig from five years ago. It’s a photo from a page in her diary, but this frame was used in her directorial debut A Death in The Gunj. Shown as a page from the sensitive Shutu’s diary. These words: eulogy, esoteric, elliptical, epiphany, coupled along with, of course, the corpse of a moth, come to define his life. If you’ve not, I invite you to watch the movie and allow your senses to be serenaded. We are all waiting for Koko’s next movie with bated breath.